An exceptionally volatile new crude oil produced by fracking operations in North Dakota is being stored at United Riverhead Terminal in Northville, RiverheadLOCAL has learned.

The light crude, extracted from the Bakken Shale oil field in North Dakota, which produces more than 1 million barrels per day, is more gaseous, has a much higher vapor pressure than most oils and has a lower flashpoint. That’s what makes it more flammable and combustible than other crudes, according to critics.

Bakken crude has been identified by federal and state regulators as posing “an imminent and substantial” danger to public safety, following explosive rail accidents that killed dozens of people, destroyed dozens of homes and forced the emergency evacuation of hundreds of homes endangered by fires that burned for days.

The incidents prompted the U.S. Department of Transportation to issue a safety alert about Bakken last year, which was followed by an alert to first responders issued by the International Association of Fire Chiefs.

Nevertheless, the introduction of Bakken crude at the Riverhead facility in 2014 was unknown to local officials and first responders, including the Riverhead fire marshal, the Riverhead Fire Department chief, the town supervisor and members of the town board, who all said they were unaware that URT began accepting and storing Bakken in Northville until asked about it by RiverheadLOCAL.

Similarly, L.I. environmental activists were in the dark about Bakken being stored in Riverhead.

“This is scary stuff,” said L.I. Pine Barrens executive director Richard Amper, referring to the “extreme volatility” of the Bakken, which he said he’s become familiar with through his work on the board of Environmental Advocates of New York.

“And let’s not forget it’s being stored in a state designated special groundwater protection area,” Amper said.

“What are they thinking?”

Citizens Campaign for the Environment executive director Adrienne Esposito said she found the news “alarming.”

“You don’t want to scare the public but you don’t want to deceive them either. The accident record of this material is quite disturbing,” Esposito said.

“Ignorance isn’t bliss. Ignorance is dangerous.”

A ‘virtual pipeline’

The Bakken crude is off-loaded at the terminal’s deep-water platform in the Long Island Sound, located one mile off the Northville shore, and pumped via pipeline to tanks on United Riverhead’s 286-acre site. It’s stored there until it’s shipped back out the same way — from tank to pipeline to platform, where it’s loaded onto a ship and transported to one of the East Coast refineries.

It does not leave the terminal by truck, according to both the terminal operator and the N.Y. State Department of Environmental Conservation, which confirmed that “there is no over-land transport” of the Bakken on Long Island.

“Storage for it is much in demand,” URT general manager Scott Kamm said in a phone interview last week.

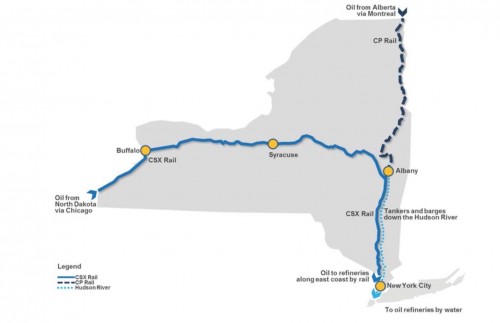

The Bakken is transported by rail from North Dakota to the Port of Albany, where it’s transferred to tankers and barges and shipped down the Hudson River, through New York City to refineries in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware, Kamm said. Some of it is stored at the Riverhead terminal when it can’t be brought directly to a refinery.

The boom in hydraulic fracking crude oil production in North Dakota has billions of gallons of Bakken crude transiting the Hudson River annually, turning it into a ‘virtual pipeline,’ say critics and environmental advocates.

While there have been no accidents resulting in explosions or fires during the marine transport of Bakken, there are very real safety and environmental concerns. These range from the very real potential for catastrophic explosions and fires associated with handling and transporting Bakken, to air emissions of possibly toxic chemicals, and spills that could do severe and perhaps permanent damage to the federally designated L.I. Sound estuary and the region’s drinking water aquifer.

“We get all of our drinking water from beneath our feet,” Amper said. “We don’t need to store contaminants above it. It’s preposterous.”

There have been marine accidents and spills — though none so far in New York. One spill last year shut down 65 miles of the Mississippi River for two days.

The transit of Bakken in the L.I. Sound worries Esposito.

“There are clear signs that the L.I. Sound is recovering,” she said. “One incident with this could be devastating.”

‘Almost like a soda can’

Gov. Andrew Cuomo responded to catastrophic rail accidents and the increasing transport of Bakken through New York with executive order 125, signed in January 2014. Cuomo directed five state agencies to immediately conduct a coordinated review of the state’s crude oil incident prevention and response capacity and make recommendations for changes needed to “better prevent and respond to incidents involving the transportation of crude oil and other petroleum products by rail, ship and barge.”

The state agencies — the DEC, the health department, transportation department, the homeland security and emergency services division and the state energy, research and development authority — produced two reports last year in response to the executive order.

“Bakken crude oil is inherently volatile with a flash point and vapor pressure similar to gasoline,” the first report, issued in April 2014, said. “An additional and serious danger is often the amount of dissolved natural gas and volatile organic compounds within the crude. This gas affects the vapor pressure of the crude. When contained in tank cars or other vessels, the vessel itself can become highly pressurized, almost like a soda can,” according to the report. “Materials with high vapor pressures tend to burn more violently because the liquid can change into vapor more readily, feeding a fire.”

The April 2014 report made recommendations to “strengthen the state’s preparedness” and a second report, released in December, updated the governor on progress made so far.

Among the April report’s recommendations was increasing training and drill opportunities. On Nov. 4, 2014, the DEC held tabletop drills with United Riverhead at its Northville terminal, according to the December follow-up report.

Fire marshal: Northville terminal ‘well-equipped’ to store Bakken

The December report said the state has also increased inspections of all facilities handling Bakken.

The December report said the state has also increased inspections of all facilities handling Bakken.

United Riverhead Terminal is inspected by the U.S. Coast Guard, the federal Department of Homeland Security, the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the state DEC, as well as by the Riverhead fire marshal, URT’s general manager Kamm said.

URT was the site of an unannounced drill by the EPA in June, he said.

“They hand you a scenario and you have four hours to deal with it,” Kamm said. “We had no trouble,” he said.

“Minor issues” were noted during a “spill prevention, control and countermeasure” inspection at the Riverhead terminal in May 2014, according to the state’s December crude update. “All but one had been rectified” the report said. It did not provide details on the issue.

It is not clear how much Bakken crude is being stored at the Riverhead terminal. The facility’s license documents are not posted online and are exempt from disclosure under the state’s Freedom of Information Law due to homeland security concerns, according to the DEC.

“The facility is authorized to store Bakken crude oil as well as other heavy/light crude oils in six tanks,” the agency said in an emailed response to questions late last month. “Currently, the facility is actively storing crude oils in 2-3 tanks.” There are 20 tanks at the terminal.

The facility is required to advise DEC of any change in products to be stored there “so that DEC staff can determine if they can safely store and handle the product in accordance with the regulations,” according to the agency. “If so, DEC amends and reissues their license accordingly.”

Riverhead Fire Marshal Craig Zitek said the tanks where volatile petroleum products are stored have foam suppression systems and other safety features to prevent disasters. Also all tanks have containment around them, he said.

While the fire marshal said he was unaware of the Bakken when first asked about it by a reporter late last month, on Oct. 1, he said he’d gone up to the facility after learning about the Bakken storage, performed an inspection and spoken to management there.

“They’re well-equipped to store it,” Zitek said.

Riverhead Fire Chief Joe Raynor was perturbed the department wasn’t notified of the new type of petroleum product being stored there, especially if it comes with increased or different kinds of risks — to the surrounding community and to first responders.

But according to Zitek, “It’s no different than gasoline, it’s less volatile, really.” He said United’s predecessor stored gasoline there for many years.

Air emissions concerns

All major oil storage facilities must obtain air permits from the DEC, which regulates air emissions.

There have been reports of high concentrations of benzene vapors during “lightering” operations — the off-loading of oil from a ship. Benzene, a known human carcinogen, is designated by the EPA as a hazardous air pollutant; its vapors can cause headaches and dizziness.

“[H]uman exposure to benzene may result in increased risk of leukemia, birth defects, pulmonary edema … laryngitis, and bronchitis. Benzene can remain in the air for several days once it is released into the air,” according to documents filed in a lawsuit brought against the DEC last year by Earth Justice.

The suit, still pending in State Supreme Court, seeks to set aside the DEC’s determination that the Albany terminal’s expansion will not have a significant environmental impact and to compel the preparation of an environmental impact statement.

Residents in an apartment complex near the Global Partners Albany terminal are complaining of headaches and dizziness from a “heavy burning odor” coming from the terminal when Bakken is being transferred to ships, according to the lawsuit, filed on behalf of the tenants association, Riverkeeper, the Sierra Club and the Center for Biological Diversity.

Northville Beach is no stranger to odors emanating from the Riverhead terminal, says Northville Beach Civic Association president Neil Krupnick. The neighborhood was plagued by a terrible odor in January, and the revelation that Bakken crude is being stored at URT now has Krupnick wondering if Bakken was to blame. At the time of the odor, which enveloped the shorefront community adjacent to the terminal for more than 36 hours, a tanker was off-loading at the URT platform.

For Krupnick, the incident is an example of regulatory oversight that leaves much to be desired. He said DEC staffers told the civic group members last fall “that they count on URT to do a fair amount of self-regulating.”

But in mid-January, “after noxious fumes were released into the air for well over 12 hours and could be smelled a mile and a half away, URT did nothing to stop it until we contacted the DEC,” Krupnick said.

“That’s not self-regulating; that’s hoping the neighbors don’t notice or say anything.”

Krupnick was unable to reach anyone at the DEC on the evening of Jan. 13, when the odor became “unreal.” He emailed the agency on Jan. 14 and in a return email the same day, a DEC environmental program staff member acknowledged that the operation at the platform was causing the odor.

The DEC said they talked to URT management who “instructed the vessel operator making the delivery to take the necessary steps to reduce/eliminate the odors (i.e. reduce rate of delivery and since it was not necessary, stop heating the petroleum). URT will be monitoring the off-loading to ensure the vessel operator complies with their instructions.”

The odor persisted and after additional complaints to the DEC, the agency made a site visit the following morning, on Jan. 15.

“No odors were detected downwind of the operation at Iron Pier Beach Park or in the nearby area along Sound Shore Rd.,” DEC environmental engineer Shaun Snee wrote in an email to Krupnick.

Yet, Krupnick said, the odor was bad at mid-day and later worsened and spread to a wider area. He again complained to state regulators.

“We would like to know why it’s acceptable for such a large amount of fumes to be released over a 12 hour period and why it takes a neighbor’s complaint to get the facility to notice that it’s polluting the environment?” Krupnick asked.

By then, his wife Ann and others in the area were suffering with headaches, irritated eyes and dizziness.

Government ‘asleep at the switch’

Krupnick, a town board candidate who last year organized opposition to a proposal by United to build ethanol storage tanks in Northville so it could begin storing gasoline and dispensing it at its truck rack there, said he was troubled town officials knew nothing about Bakken being on site.

His sentiment was echoed by his running mate, supervisor candidate Anthony Coates.

“United not telling us there’s Bakken in Riverhead, is like Khrushchev not telling us there were missiles in Cuba,” Coates said. “This is a huge story and this is exactly what’s wrong with Town Hall. Our government is asleep at the switch.”

Supervisor Sean Walter said on Saturday, URT’s failure to notify town officials was “unacceptable” and something he would be looking into. He said the terminal operator is only required to notify the DEC of petroleum products it is handling there.

“The DEC, not the town, regulates bulk storage,” Walter said.

Councilwoman Jodi Giglio said Monday she was disappointed the town was not notified. “That’s very bad,” she said.

Councilman James Wooten said he was not familiar with Bakken crude and would research it.

But Riverhead officials are not alone. There are no federal or state rules requiring public notice when Bakken is brought into or through a community, despite several fiery accidents involving Bakken that killed 47 people.

Local government officials in cities and towns across the country have complained about not being told of shipments into or through their jurisdictions.

Last year the federal transportation department issued an emergency order requiring railroads to alert states about oil trains originating in North Dakota. But rail companies, worried about community backlash and terrorist sabotage, resist providing details.

Is Bakken rail shipment in Long Island’s future?

Coates says he’s deeply troubled by United’s access to a rail line at its EPCAL facility and company founder John Catsimatidis’ announcement that he’s planning to build a pipeline linking the Northville terminal with the United Metro terminal in Calverton.

At a Riverhead Town Board meeting in May Catsimatidis said he has plans to build a pipeline connect the Northville terminal and the Calverton biofuel terminal, which United acquired in 2013. He said he also planned “fully connect” the EPCAL rail spur to his Calverton site.

His plans would reduce truck traffic on local roads, Catsimatidis said.

“My concern is, before I authorize spending tens of millions of dollars I want to just make sure the town does the right thing by everybody, not just by 12 people complaining about bad scenery,” he said, swiping at complaining residents who packed the Town Hall meeting room twice to protest the oil tycoon’s plans to begin dispensing gasoline to tankers at Northville.

After two marathon, contentious public hearings Catsimatidis withdrew the application to expand his company’s pre-existing, nonconforming use.

The town supervisor later said he had “suggested that they withdraw the application and resubmit it at a later date with a lot more information.”

“We have no way of knowing what his plans entail,” Coates said of Catsimatidis’ vision for a Long Island pipeline-rail line link.

“Imagine full exchangeability of deadly Bakken by pipeline over our farms and drinking water, then imagine this volatile product going out by rail through our EPCAL subdivision,” Coates said. “One mistake anywhere in the supply chain could cripple Riverhead for years to come. What are they thinking?”

Coates took a special jab at Giglio, the Republican candidate for supervisor this year in a three-way race with Walter, who’s running on the Conservative line, and Coates, a Democrat.

As a permit expediter, Giglio represented Metro Biofuels when it bought and opened the site in the Calverton Enterprise Park, according to the councilwoman’s ethics disclosure report filed with the town clerk.

Coates questions whether Giglio’s “deep business relationship” with Metro continued after its acquisition by United. United was represented in Riverhead by former councilman Victor Prusinowski, who Giglio says took over many of her clients after she was elected councilwoman in 2009.

Giglio said this week she has no business relationship with United.

While there are safety and environmental concerns about Bakken being delivered via the L.I. Sound to United terminal in Northville, Coates said, the dangers of shipping Bakken by rail are well-documented by several deadly accidents and catastrophic fires.

“A few weeks ago a freight train derailed on the New York and Atlantic line to New York.” Coates said. “Imagine if it contained Bakken.”

A DEC spokesperson said last week the agency has had “no discussions or correspondence regarding the installation of a pipeline between the United Riverhead and United Calverton Terminals.”

Editor’s note: Following the publication of this story, Councilwoman Jodi Giglio contacted the author to deny she said she had a personal friendship with John Catsimatidis. She said she previously stated she was invited to his birthday party. “But the whole town board was invited,” she said. “He invites all the politicians.”

The survival of local journalism depends on your support.

We are a small family-owned operation. You rely on us to stay informed, and we depend on you to make our work possible. Just a few dollars can help us continue to bring this important service to our community.

Support RiverheadLOCAL today.